This is an idea which came about on the road during my trip back from Hood River, Oregon during the past week. It started as a fun brain teaser to determine the amount of time it would take to reach a destination given a certain amount of miles, going a certain miles an hour.

Doing this is easy, given the MPH and the amount of miles to your destination. Also, every map application gives an approximate that can outperform your own calculation due to other factors, like traffic.

Working out some of the numbers, I realized that there is an easy way to approximate small differences in time to destination. It uses only basic levels of algebra and calculus, and is fairly generalizeable with a simple proof. Overall, I found this a fun and insightful derivation of simple equations.

Algebraic Method

Let us start with a very simple situation relating to gas mileage:

Given that you have traveled 10 miles and have used 1.0 gallons, what is your gas mileage?

\[\frac{10mi}{1.0gal} = 10\;mpg\]Instead, you now have traveled 10 miles and have used 1.06 gallons:

\[\frac{10mi}{1.06gal} = \;?\]Using a calculator, it is $9.43396\;mpg$. However, I can’t use a calculator because I don’t want to use it (while driving). So, what do we do?

\[\frac{10mi}{1.06gal} = \frac{10}{1+0.06}\]Let the $x = 0.06$, so

\[\frac{10mi}{1.06gal} = \frac{10}{1+x}\]We use this simple distribution equation:

\[(a+b)(a-b)=a^2-b^2\]Now applied to $1+x$, assuming x is a small amount:

\[(1+x)(1-x)=1-x^2\approx1\] \[1-x\approx\frac{1}{1+x}\]This means that an increase gas of amount x (percent) equates to a decrease in that same amount, x, in an approximate sense. This is of course, assuming the change in percentage is a small amount, and therefore the $x^2$ term can be ignored.

In the case of our problem, where x is 6 percent,

\[\frac{10}{1+x}=10(1-x) = 10(1-0.06)= 9.4\]This is a pretty good approximation. 9.4 is a little less than actual because we remove the $x^2$ term. With it,

\[\frac{1}{1+x} = \frac{1-x}{1-x^2}\]This isn’t something we can calculate in our head, but $x^2$ is always positive, so the denominator would be less than one, making the actual value larger than our approximation. This makes sense.

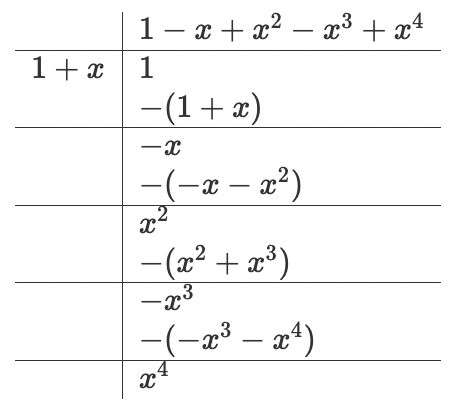

Let’s explore this a bit further. What if we just divide $1$ by $1+x$, using generalized long division?

There is a pattern here. It switches between +,- and the exponent keeps increasing. It’s a geometric power series! This converges when $\mid x\mid < 1$, or else the larger exponents will just swing wider and wider.

Using Calculus

Let us verify, using calculus, with a Taylor series approximation.

The Taylor series for a function $f(x)$ around $x = 0$ is given by:

\[f(x) = f(0) + f'(0)x + \frac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2 + \frac{f'''(0)}{3!}x^3 + \cdots\]For $f(x) = \frac{1}{1+x}$, we have:

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{1+x}\] \[f'(x) = -\frac{1}{(1+x)^2}\] \[f''(x) = \frac{2}{(1+x)^3}\] \[f'''(x) = -\frac{6}{(1+x)^4}\]Evaluate at $x = 0$:

\[f(0) = 1\] \[f'(0) = -1\] \[f''(0) = 2\] \[f'''(0) = -6\]Taylor series up to the third term:

\[\frac{1}{1+x} = 1 - x + \frac{2}{2!}x^2 - \frac{6}{3!}x^3 + ...\] \[\frac{1}{1+x} = 1 - x + x^2 - x^3 + ...\]What is really cool is that the $nth$ factorial is cancelled out by the $nth$ derivative constant for every element, resulting in the same answer as when we performed long division. We will come back to this.

Let us prove that this expression is correct:

First multiply both sides by $1+x$

\[1 = (1+x)(1 - x + x^2 - x^3 + x^4 + ...)\] \[1 = (1 - x + x^2 - x^3 + x^4 + ...)+\] \[\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;(x - x^2 + x^3 - x^4 + x^5 + ...)\] \[1 = 1 \text{, as required, since it cancels out infinitely.}\]As we have shown, there are both algebra and calculus can derive this approximation, and both are very cool approaches.

Broader Use

This can be used for many other cases, such as if you are given the miles to your destination and you also know your speed (miles/mph). For example, if you have 300 miles to your destination and you are traveling 60 miles per hour, it would take 5 hours $(300/60)=5$.

This is odd. The original equation was set up in a way that you would want a small percentage deviation away from one. ie, $\frac{1}{1+x}$ This is easily generalizeable though, as that percentage is just scaled in order to fit the equation, as shown below:

\[\frac{360}{60+x} = \frac{360}{60(1+\frac{x}{60})}\]Let $y = \frac{x}{60}$:

\[= \frac{360}{60(1+y)} = \frac{6}{(1+y)},\]where you just need to replace the y eventually.

Using algebra, approximation has become very versatile.

Tangents and Remarks

This is not directly related to the topic of this post, but there are a couple interesting corollaries or other ideas that stem from this.

First, the relation between the exponential power/Taylor series (what we looked at) and the cos and sin counterparts.

The Taylor series expansion for $\sin(x)$:

\[\sin(x) = \sin(0) + \cos(0)x + \frac{-\sin(0)}{2!}x^2 + \frac{-\cos(0)}{3!}x^3 + \frac{\sin(0)}{4!}x^4+...\] \[\sin(x) = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!}+...\]The Taylor series expansion for $\cos(x)$:

\[\cos(x) = \cos(0) + \frac{-\sin(0)}{1!}x + \frac{-\cos(0)}{2!}x^2 + \frac{\sin(0)}{3!}x^3 + \frac{\cos(0)}{4!}x^4 +...\] \[\cos(x) = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!}+...\]They look very similar. However, when higher derivatives of the function at $x=0$ are calculated, the cos and sin go through the four part cycle of its derivatives: sin, cos, -sin, -cos, and then sin again. Unlike the earlier Taylor series, the numerator does not accumulate a constant number, so the factorial on the bottom is not cancelled out. This means that the sin and cos converge relatively faster since the numbers become smaller and a much faster rate.

Euler’s Formula:

\[e^{ix} = \cos(x) + i\sin(x)\]The Taylor series expansion for $e^{ix}$:

\[e^{ix} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(ix)^n}{n!}\] \[e^{ix} = 1 + ix - \frac{x^2}{2!} - i\frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + i\frac{x^5}{5!} - \cdots\]Separate and group the real and imaginary parts in the Taylor series expansion of $e^{ix}$:

\[e^{ix} = 1 + ix - \frac{x^2}{2!} - i\frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + i\frac{x^5}{5!} - \cdots\] \[e^{ix} = \left( 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \cdots \right) + i\left( x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \cdots \right)\] \[e^{ix} = \cos(x) + i\sin(x)\]This is not to prove or derive Euler’s Formula. $e$ is used to algebraically define $sin/cos$, so therefore it is weird to use it in this way. However, depicting Taylor expansions of $sin$ and $cos$ can reveal similarities between these functions and the $e$.

And now, we can see that this equation used throughout all the electrical engineering classes can explain connections between exponential and sinusoidal function’s Taylor series. An interesting new perspective on a widely used equation.

Something cool is that Taylor series are what older calculators used to approximate trigonometric functions. They would take known values at angles such as 30, 45, 60 degrees and calculate with the offset of that. I have trouble finding documentation on that, but in modern times many calculators use the CORDIC algorithm, or a decimal CORDIC technique, which is outside the scope of this post (see link).

Overall, this post was an exploration of simple algebra and calculus, and a good mathematical review that I believe many young engineers need. Sometimes thinking about the world around you in an analytical way is a great exercise for the brain, and it is fairly useful as well.